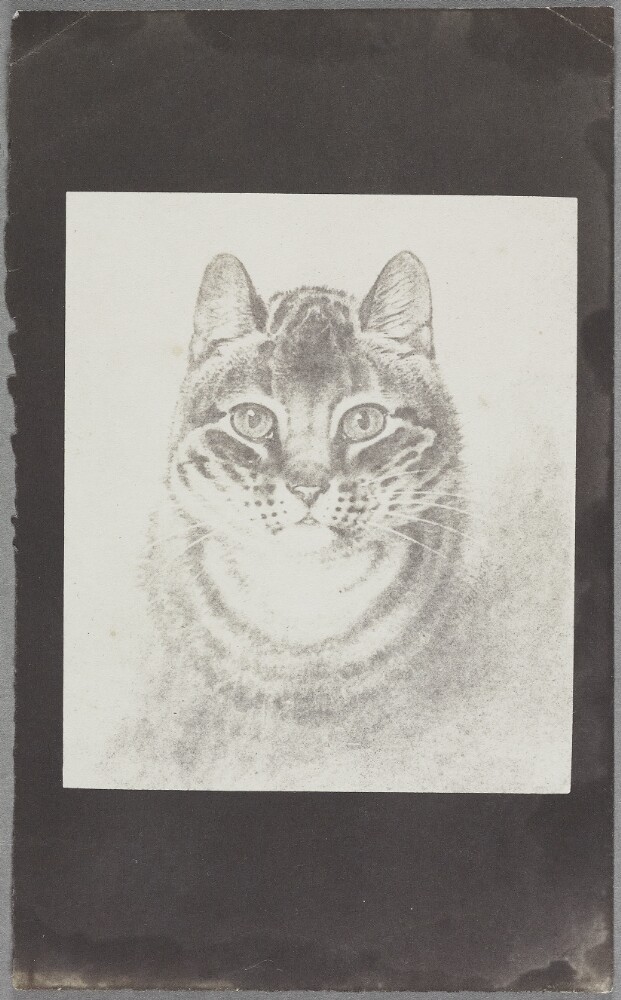

Copy of a Print by Mr Burbank, head of a Cat

This might look like a drawing, but it is, in fact, a photographic print. In the mid-1830s William Henry Fox Talbot made major breakthroughs in experiments in photography, successfully printing ‘positive’ prints from one negative. He named this the calotype process, after the Greek word ‘Kalos’ meaning beauty.

Talbot experimented extensively with using photography to reproduce different kinds of images, capturing scenes from life, as well as reproducing the printed page.

This cute kitty is believed to be a copy of ‘a favourite cat’ by J.M. Burbank, an artist who exhibited animal pictures during the 1830s in Britain.

Miss Mary Mitford’s dog

In 1840s, Talbot’s new photographic process was made available to the public at a select number of exclusive studios.

In 1847 celebrity author Mary Mitford visited one such studio operated by the photographer Nicolaas Henneman, to sit for a portrait .

Mitford brought along her dog for the occasion, insisting that her pet sit for their own picture. Henneman was sceptical of a dog’s ability to sit still for the photograph. However, much to his surprise the dog sat perfectly still for four minutes ‘as if he was dead’ . Judging from the finished picture, he looks like he was extremely bored.

The ‘dog’uerrotype

Calotypes weren’t the only photographic format on the market in the 1840s. In fact, much to Talbot’s dismay, the invention of photography in France was announced to the world by Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre in 1939. Daguerre developed a way of taking pictures using a polished silvered plate and a camera. This produced a single image printed directly onto a plate with astonishing clarity, named the daguerreotype.

Daguerreotype studios offered people the opportunity to create a one-of-a-kind keepsake of their loved ones. However, in our ‘dog-uerreotype’ we can see that this little pet wasn’t so keen on sitting still for their portrait—the dog’s movement has caused the blurred lines around his face in the image.

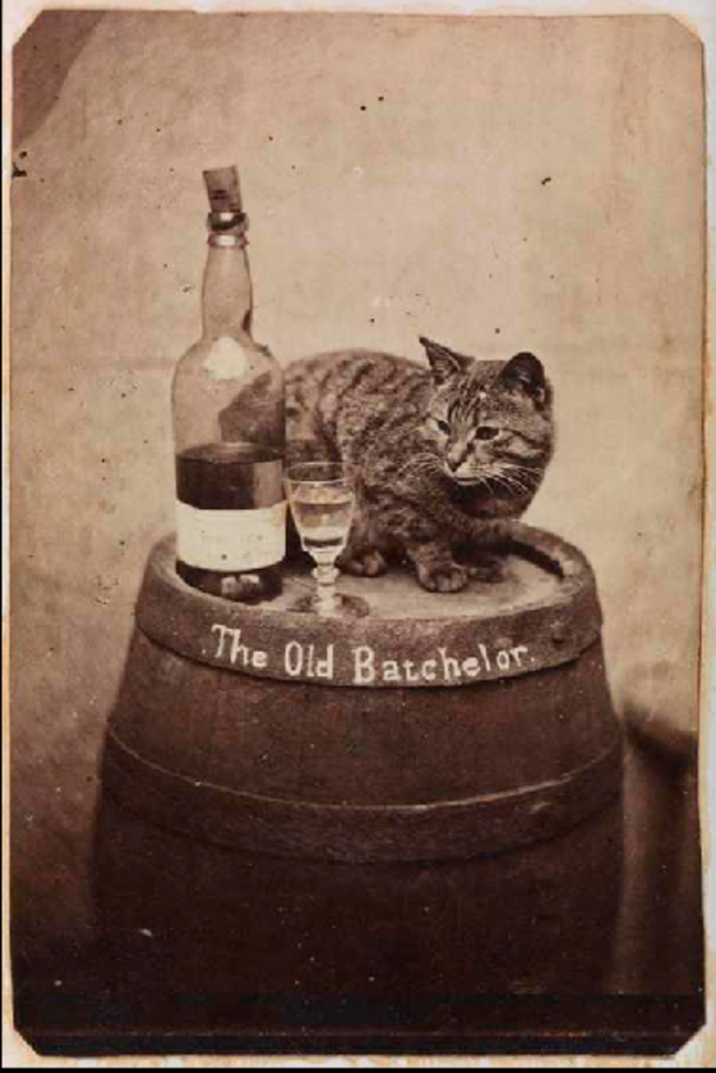

The Old Batchelor

Introduced in the 1860s, the cabinet card become the next big photographic trend. Much like its smaller companion the carte-de-visite , cabinet cards were a highly social form of media, designed to be shared by friends and family. We can imagine this image being shared around the fire in a Victorian parlour. Perhaps it was made in reference to a play of the same name? The distinctive brown hue of the cabinet card tells us it was produced using the albumen process—a way of printing photographs using a thin sheet of paper and egg white . Albumen prints produce a sharp and rich image, perfect for capturing senior kitties as handsome as this one.

These days, we’re more likely to snap our favourite pets using our phone cameras than time-consuming film processes—but the impulse to capture photos of our furry friends remains the same.