“I mean, photography is alright if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops – for a split second. But that’s not what it’s like to live in the world.”

– David Hockney

You’d be forgiven for thinking that David Hockney doesn’t like photography very much. Bradford’s most famous visual artist has had some choice things to say about photography’s limitations over the years, and yet he has dedicated many, many hours to creating stunning works of photographic art.

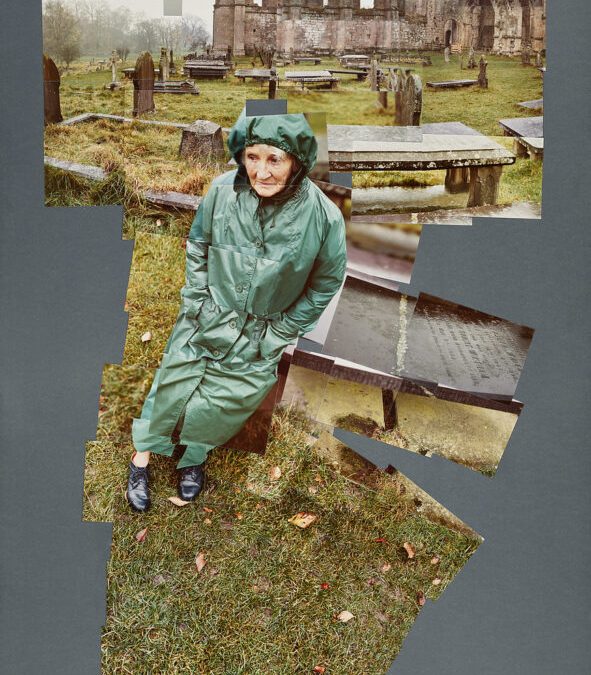

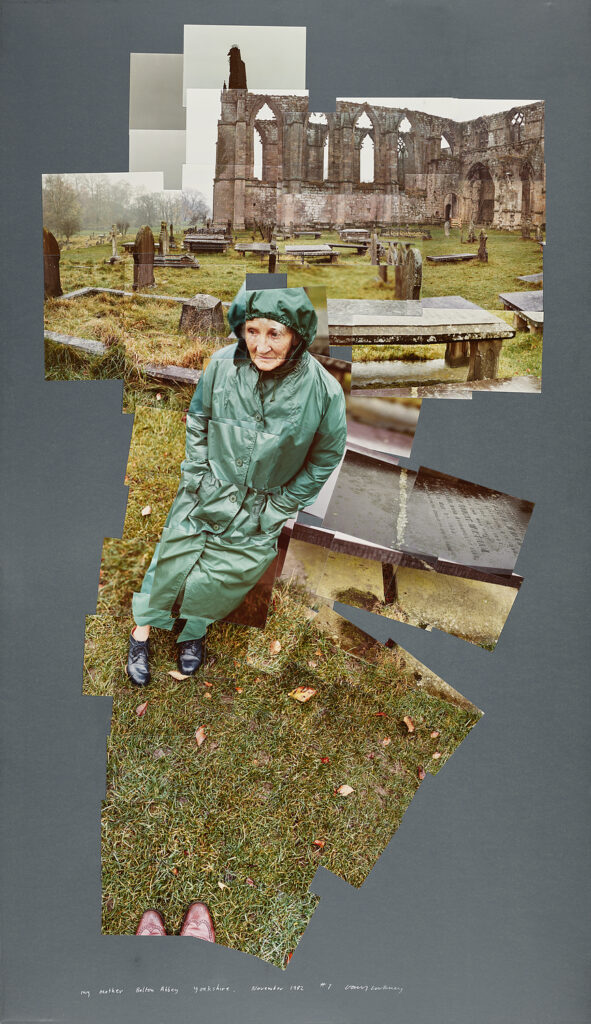

Hockney’s photo-collages, or ‘joiners’, are some of his most recognisable artworks – huge scenes made up of dozens of overlapping photographs, like this portrait of his mother, Laura, perched on a tombstone at Bolton Abbey.

Hockney developed his joiner method in direct response to what he saw as photography’s biggest failing: its inability to reflect the complexity of how we really see the world around us. As he explained in a 1983 episode of The South Bank Show, he became frustrated with only being able to capture “frozen moments” with a camera – split seconds of action, leached of life.

“I’d become very, very aware of this frozen moment that was very unreal to me. The photographs didn’t really have life in the way a drawing or painting did, and I realised it couldn’t because of what it is. Compared to Rembrandt looking at himself for hours and hours and scrutinising his face and putting all these hours into the picture that you’re going to look at – naturally there’s many more hours there than even you can give it. A photograph is the other way round. It’s a fraction of a second, frozen, so the moment you’ve looked at it for even four seconds, you’re looking at it for far more than the camera did. And it dawned on me that this was visible, and the more you become aware of it the more this is a terrible weakness. Drawings and paintings do not have this.”

Hockney’s joiners were his antidote to the frozen moment, a way of imbuing his photography with action and a sense of time passing. An excellent example is one of the gems of our collection, currently on display in our temporary exhibition David Hockney: Pieced Together.

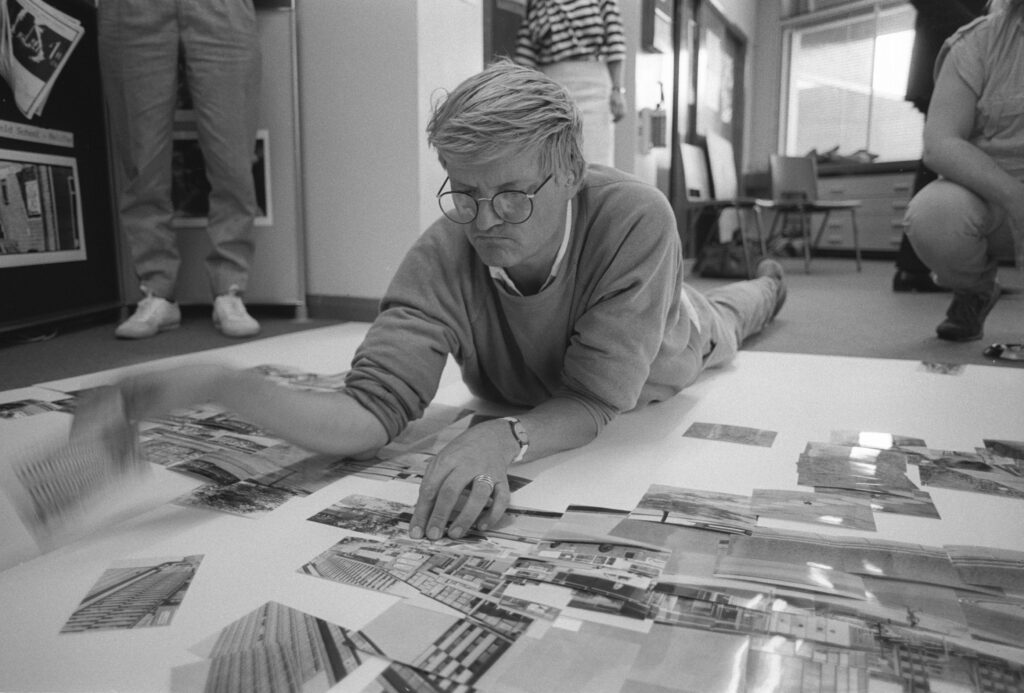

In the summer of 1985, Hockney made Bradford, Yorkshire, July 18th, 19th, 20th 1985, a joiner of this very museum, then called the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television. He took dozens of photographs from the top of a platform lift, attracting the attention of museum staff, passers-by and people working on the roof of the Alhambra theatre behind him. He then sent the film to a local photo shop to be printed, before stretching out on the floor of a museum office to put the joiner together.

Hockney took the joiner photographs in horizontal lines from left to right, moving the camera a little bit between shots. You can tell the direction he moved in because the same woman wearing a beige jacket appears several times as she walks past the museum, something that Hockney could only have caught by following her path with his camera.

In his 1983 interview for The South Bank Show, Hockney explains that the sense of time passing in his joiners “is not an illusion. It is real and accounted for in the number of pictures. You know it took time to take them, wait for them [to be printed], put them down and so on.” The woman in a beige jacket is a clear example of this phenomenon at work. Because we see the same person repeatedly, we know that it took Hockney as long to take those photos as it did for her to walk by. Similarly, faster-moving vehicles are fractured across several photographs as Hockney tried to snap them before they sped past. In short, we can see the time Hockney spent taking the photographs in the photographs themselves.

While true for all his joiners, Hockney’s notion of being able to see the time it took “to take them, wait for them, [and] put them down” is even more relevant to the photographs in this particular joiner.

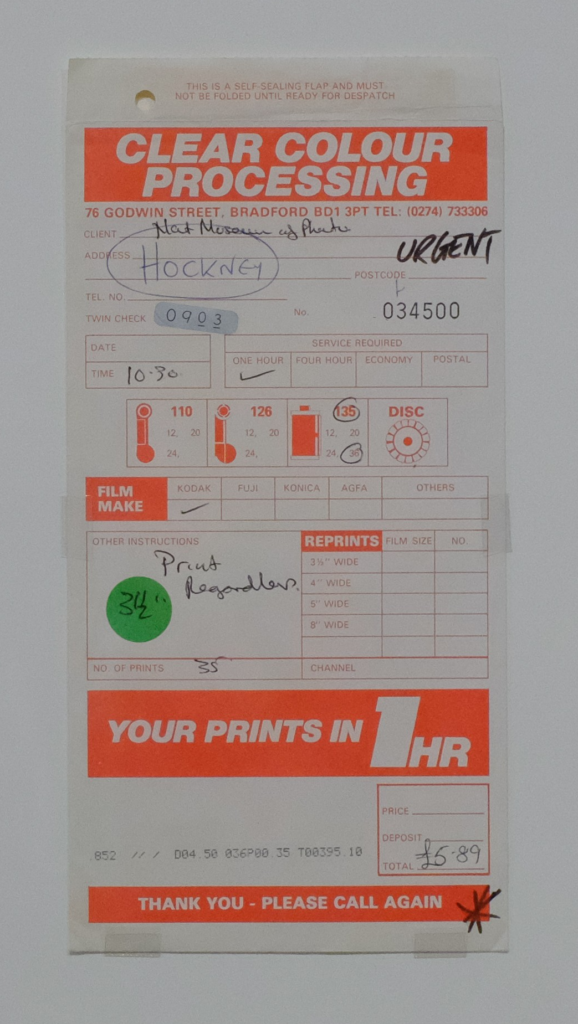

Unlike today’s digital cameras, film cameras had no preview screen or way of scrolling through the images already taken – Hockney had to rely on his memory of what he had already photographed when lining up his next shot. It was only once the photographs were printed and the joiner assembled that the overlaps and relationship between the images became clear. When assembling the museum joiner, Hockney discovered a problem – he didn’t have enough photographs to complete the scene. He went up the platform lift again the next day, took some extra photographs, and sent the film to Clear Colour Processing, a shop in the Kirkgate Shopping Centre which offered one-hour printing. The original processing envelope has ‘URGENT’ scrawled at the top, along with a note of the 35 extra photos he took.

Hockney then incorporated the extra prints into the joiner alongside the ones he had already taken. This is why there are three dates in the joiner’s full title – the first set of photographs were taken on the 18th of July, he began assembling the joiner on the 19th, and the last batch of images was taken and the joiner completed on the 20th.

When you look closely at the joiner, there are clues that the photographs were taken on two separate days. The sky is overcast on the left while the sun is shining on the right, and in some pictures the pavement is wet, but dry on the rest.

One set of photographs is also more matt in appearance because the two different printing shops Hockney visited used different paper (you can see in the image below that the photo with the section of blue sky is much shinier).

As well as revealing the passing of time through the obvious work and attention that went into creating them, joiners manipulate time in the way they encourage us to look at them.

When we look at the real world, we move our eyes and bodies to scan our surroundings and focus on the things that interest us. It takes time and events change in front of our eyes. It is this real-life experience of viewing a scene that Hockney tries to replicate when we look at his joiners, using different arrangements of images to capture our attention for different amounts of time.

For example, in the museum joiner, we’ve already seen how Hockney catches half a car as it moves quickly past the camera. In contrast, he includes multiple photographs of the same bystanders to show how their positions and facial expressions change over the course of a conversation. Not only do we know that the two events would have happened over different lengths of time (fast car, long chats), but we are likely to spend more time looking at the photographs of the people than the car, if only because there are more individual images to scan and make sense of.

Looking at a Hockney joiner is a lot like sitting on a bench and watching the world go by. You can sit back and let the busyness of the whole scene wash over you, or you can lean in and get lost in all the details. Either way, it’s time well spent.

You can see ‘My Mother, Bolton Abbey, Yorkshire, Nov. 1982’ and ‘Bradford, Yorkshire, July 18th, 19th, 20th 1985’ in David Hockney: Pieced Together at the National Science and Media Museum until 18 May 2025.