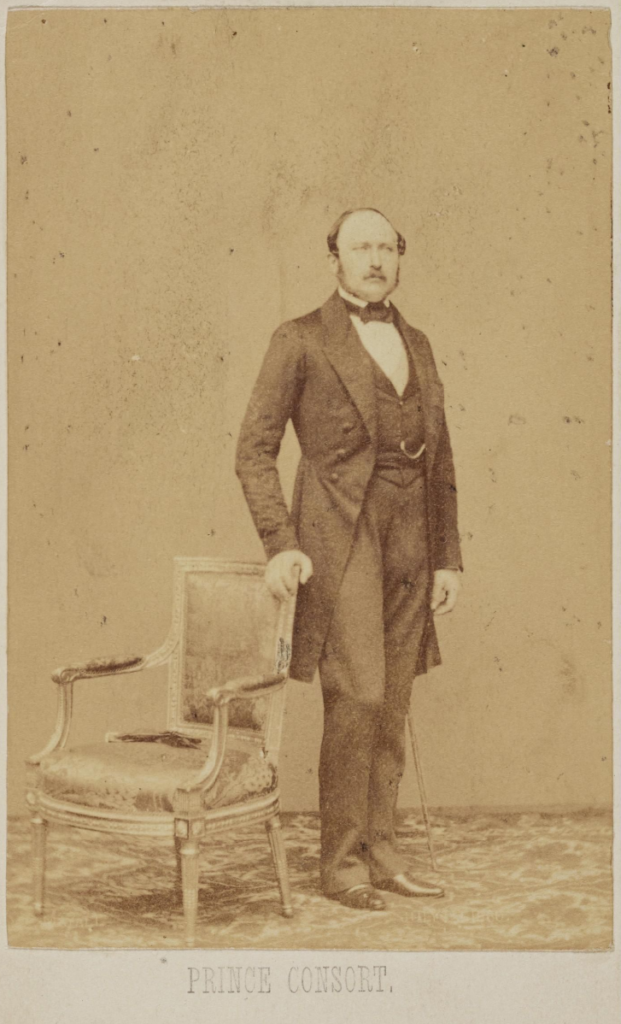

Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert were keen champions of early photography and if they lived today, I imagine they would have been among the first and most zealous Instagram users, regularly posting pics of royal rituals and routines and getting millions of likes.

Victoria had a complex and evolving relationship with photography. Initially, she was somewhat hesitant about the new medium when it emerged in the mid-19th century. But as the technology advanced and became more popular, she came to appreciate it for its ability to capture memories and document important events. She became quite fond of having photographs taken of herself and her family. She commissioned photographs to preserve family moments, including images of her children and her beloved Albert.

The Queen’s own photographs were sometimes used to create various types of photographic prints, which were quite popular in her time. She also embraced photography as a means of keeping distant relatives connected to her court. Personally, I’m grateful for how Victorians used photography to document public life, history and the social changes of their era. And I love the Victorian section of the Kodak gallery at the National Science and Media Museum!

But I have to confess, I’ve never been into David Hockney.

When I saw that the museum was putting on an exhibition of his work, I wasn’t particularly keen. What has any of his stuff got to do with science and media Better pop in and see the charming Victorian pictures again! So, I did. But when I was done with the delightful black-and-white photographs and the chubby wooden cameras in the Kodak gallery, I thought I’d pop in and see David Hockney.

I was somewhat surprised to find that the exhibition included artwork created from photographs. I knew little about Hockney and always associated his name with the swimming pool painting. I didn’t know anything about his photo collages. The exhibition, David Hockney: Pieced Together, includes a selection of Hockney’s “joiners”. Each joiner consists of multiple photographs arranged together to form a single composite image, with the intention of capturing a more true-to-life way of seeing than one photograph can offer.

I used my phone to take a photograph of one of the joiners, made of photographs of the statue of Queen Victoria, who had contributed to making photography increasingly mainstream. The irony of it did not escape me. I had been reluctant to go and see Hockney, but this one precious moment made me realise that I was part of a long lineage of creators using both science and media.

Would the museum itself exist if Queen Victoria hadn’t been excited about photography? If artists like David Hockney hadn’t continued exploring it as a form of artistic expression? If I wasn’t curious, and didn’t have a smartphone to take a picture and share my experience of art with friends? Time and space suddenly collapsed, bringing me closer to both the artist and the queen.

Interestingly, one of the key themes in Hockney’s joiners is the exploration of time and space. By using multiple photographs to capture a subject, he wanted to show the passage of time and the way our perception of space is not a singular, static moment but something that unfolds.

While Hockney initially used traditional film and Polaroid cameras, later works included digital manipulation and the use of computers to combine images. Hockney’s joiners were groundbreaking at the time and continue to influence both photography and contemporary art. I’m not an artist, but I like how Hockney’s work allows me to join him on this path of questioning our relationship with time and space.

I don’t ever stop to reflect deeply on what I do with the camera on my phone. I just tap or click, and I get another random image in my photo gallery. Is this the end of deeper work in photography in a world when everyone just clicks and taps? Do you have to be a professional artist to produce something that’s more than a lazy image made in the blink of an eye?

Hockney doesn’t appear to share my rather gloomy thoughts. In fact, he has praised the potential of digital tools, and how they make art more accessible to people who might not have traditional training or resources. He’s argued that the digital world doesn’t diminish the essence of art, but instead opens up new possibilities. It expands the scope of what art can be.

So maybe I too should be a bit more generous in my attitude to my smartphone camera. Maybe I can celebrate the brief moments when I take a photograph, share it with someone, and it brings a smile to their face. I imagine that both Queen Victoria and David Hockney would agree that, ultimately, this is what media, art and the science behind them are for—sharing and celebrating all of life.