Until recent history, the idea of carrying around a computer capable of multiple functions was unthinkable. Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) outlined the possibility, yet it look 100 more years for Alan Turing (1912-1954) to make multifunction computers a reality, designing a Universal Machine that could decode and perform specific instructions.

The first computers were large and expensive, used by academic researchers and military scientists; Turing’s pilot machine, the Automatic Computing Engine, filled an entire room. It took the invention of integrated circuits (otherwise known as silicon chips or microprocessors) in 1960 to change this. Replacing transistors, integrated circuits were very small and much more efficient, allowing for much more processing power in a portable package.

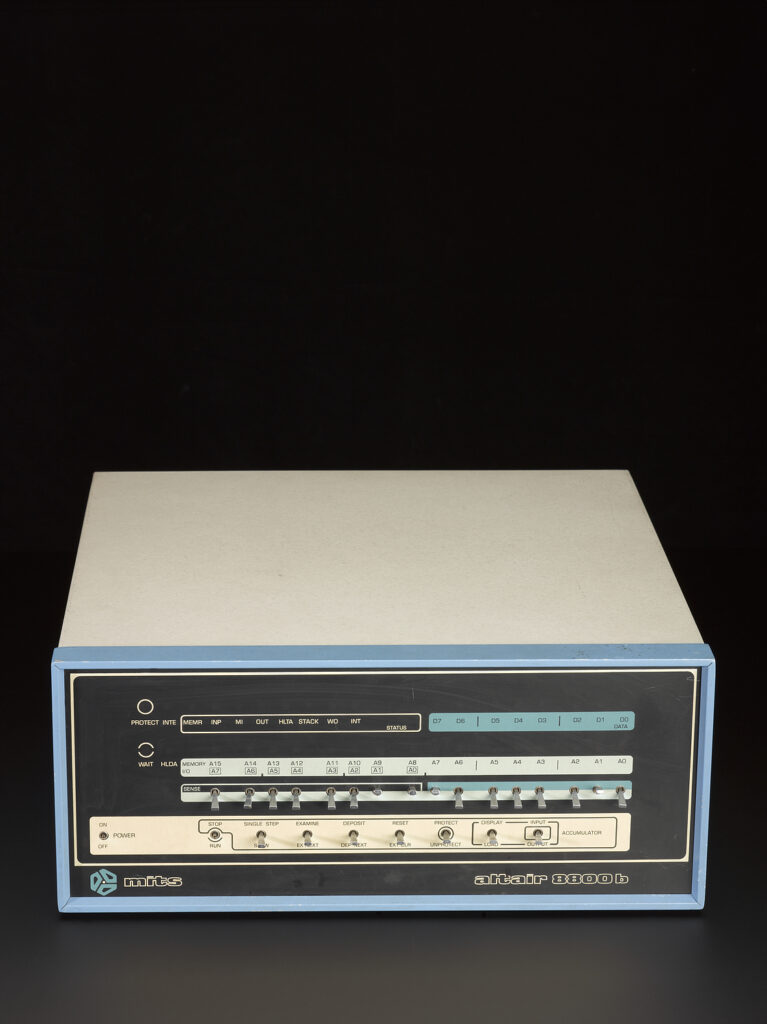

From the 1960s, hobbyists could order these smaller components in the post and build their own home computer systems, using products such as Ed Robert’s Altair kits and the MOS Technology 6502 microprocessor. It was this microprocessor that computer scientist Sophie Wilson used to develop her first commercial computer. Born in Leeds in 1957, her parents encouraged the family to create their own technology; Wilson later remembered that ‘’everybody in the house would be sitting around the table and we’d be building Heathkit multimeter [electronic kits]’ (link). During a summer break from her undergraduate degree at the University of Cambridge, Wilson used a MOS Technology 6502 to build a cow feeder for a Harrogate farming firm.

This early commercial experience meant that after graduating Wilson was hired as lead designer at the newly founded Acorn Computers. One of her first projects was the 1979 Acorn Atom, a home computer that could be bought ready-built or disassembled, offering different options for the developing market. Rival British firm Sinclair then produced similar models, ZX80 and ZX81, which were the first to be available on the high street. By the 1980s, the race to develop accessible and affordable home computers had begun, and Wilson was leading the charge.

The developing trend for home computers was noticed by the British Broadcasting Corporation. They launched their Computer Literacy Project in 1980, producing several TV series all about home computers, alongside the development of a BBC-branded computer aimed at the general public. Wilson and her Acorn colleagues worked tirelessly to make a prototype in less than a week and won the contract to produce the BBC Micro commercially.

The Micro used a programming language developed by Wilson called BBC Basic. Programming languages are how a programmer ‘talks’ to a computer to make it perform certain tasks. Wilson’s new programming language was efficient and easy to learn, inspiring a new generation to programme their own computers for the first time. By 1986, half a million Micros were sold, and they were used in 92% of British secondary schools (link). There was even a gold-plated version, produced for a magazine competition, that can be seen in the Science Museum’s Information Age gallery today.

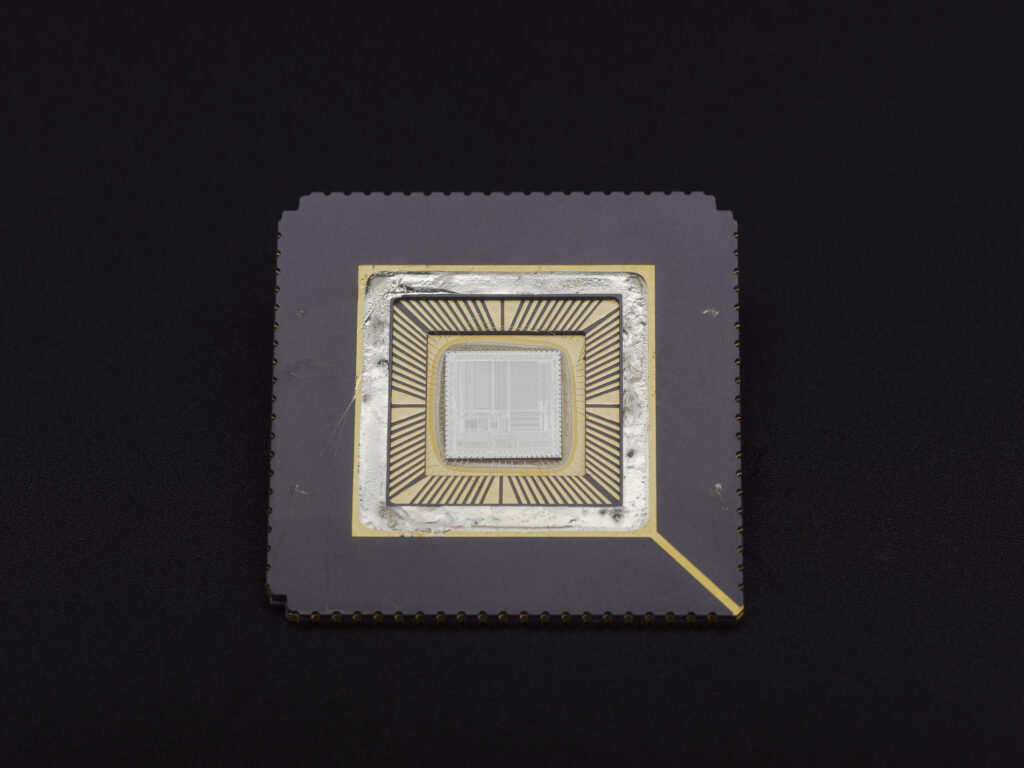

Wilson and the team then got to work designing the programme for one of the first RISC microprocessors, the Acorn RISC Machine, also known as ARM. RISC stands for Reduced Instruction Set Computer, a pioneering idea based on simplifying the instructions given to a computer, making it quicker to send those instructions so improving computer processing speed. Acorn’s ARM was first produced on the 26 April 1985 and was incredibly successful. It was designed to be inexpensive to manufacture, which resulted in a microprocessor with very low power requirements, making it fundamental to the success of smaller devices. The ARM was used by Apple in their first personal digital assistant, the 1993 Apple Newton MessagePad, and is now found in the majority of smartphones; over 30 billion processors using ARM processor architecture have been produced (link). Without Sophie Wilson, we wouldn’t have the portable computing power that we have today.

Indeed, computers in the 21st century look very different to the 1970s. Home computers are ubiquitous, but we also have portable smartphones and tablets that can roam the internet, take and send photos, stream TV shows on demand, and more. When part of Acorn Computers focusing on ARM processors was brought by Broadcom in 2000, Wilson joined them as Senior Technical Director and continues to design microprocessors today. A transgender woman responsible for several world-changing inventions (and an automated cow-feeder!), Wilson continues to inspire other women and LGBTQ+ individuals within the computing community, and recently received a Royal Society Mullard Award. Her advice to aspiring programmers: to ‘be a doer, be creative, be persistent, believe in yourself’.

The post Celebrating Sophie Wilson and 40 years of the ARM microprocessor appeared first on Science Museum Blog.