When you step into the quiet, temperature-controlled room at the National Quantum Computing Centre (NQCC) in Harwell, Oxfordshire, the first thing you notice are the three great black boxes, each containing a prototype quantum computer.

They are clad with shutters, partly to protect your eyes from powerful laser light but also to prevent heat or vibrations – even pressure waves from someone walking in – from interfering with this new and sensitive kind of computer, one that uses individual atoms to explore realms beyond the reach of conventional, ‘classical’ computers in your phone, home or office.

Under development there for the past year, the trapped-atom quantum computer remains only a promise: a machine that computes not just with logic, but with the shimmering probabilities of quantum reality. It is one of a dozen different kinds of quantum computer being studied at the NQCC.

Officially opened in October 2024, with an investment approaching £100 million, the NQCC’s 4,000-square-metre facility is Britain’s answer to a global challenge: to gather competing quantum technologies under one roof and see which are most likely to prosper.

Walk its corridors and you find a variety of approaches—superconducting circuits cooled to millikelvin temperatures with the help of theatrical chandeliers and chirping pumps made nearby at Oxford Instruments; trapped ions suspended in electromagnetic fields; photonic processors that compute with light; others that rely on silicon chips; and, glowing softly within black shutters, the neutral-atom arrays.

Indeed, the many different approaches reflect how quantum computing is in its infancy, explains Luke Fernley, a researcher at the National Quantum Computing Centre.

At their heart, quantum computers exploit the strange properties of quantum mechanics, which was developed at the start of the 20th century to describe nature at the smallest scales. “Neutral-atom-based quantum computers control the positions and properties of individual atoms,” he said. “This exquisite control allows their strange quantum mechanical properties to be exploited to perform computation.”

The theory, which is deeply counterintuitive, also says that the fate of two particles can be linked so quantum computers can do simultaneous calculations, rather than one at a time. “Think of each atom as a switch that can be on, off, or a mixture of both on and off,” he said. “These atoms can interact with each other, causing an inextricable link known as “entanglement”. This link couples the states of many atoms at once, facilitating simultaneous calculations.”

Though he started out at Durham University studying molecular quantum computers, which offer richer (but currently slower) possibilities, he believes atoms remain a fundamental gateway technology to quantum machines which all at their heart manipulate qubits, the quantum version of the 0s and 1s in an ordinary computer, which can represent both a 1 and a 0 at the same time.

Entanglement means that qubits in a superposition can be correlated with each other, enabling quantum computers to tackle difficult problems that are intractable to classical machines. Unlike the bits in a classical computer, which are rigidly on or off, qubits can occupy many states simultaneously to explore a vast landscape of possibilities at the same time.

A quantum algorithm, or program, begins life much like a classical one—as a set of logical steps—but must be reimagined in the language of quantum mechanics. Each operation is translated into an atomic recipe that dictates which qubits to entangle and how to measure the outcome. On a neutral-atom quantum computer, the computation unfolds as a carefully timed dance of photons and atoms as the quantum algorithm is translated from mathematics into matter.

By using finely tuned lasers to trap and control individual atoms, Luke Fernley and his colleagues aim to make them work together as a testbed for simulating quantum phenomena—for example, modelling molecular interactions to aid drug design. Next spring, they plan to use entangled pairs of atoms to implement quantum logic gates built from light and matter.

A central challenge lies in readout: although quantum computers can explore vast numbers of possibilities simultaneously, this parallelism cannot be directly observed. When the algorithm concludes, the delicate quantum superposition ‘collapses’ to give one answer. Useful results emerge only by running the algorithms many times to build up reliable statistics.

Atom wrangling

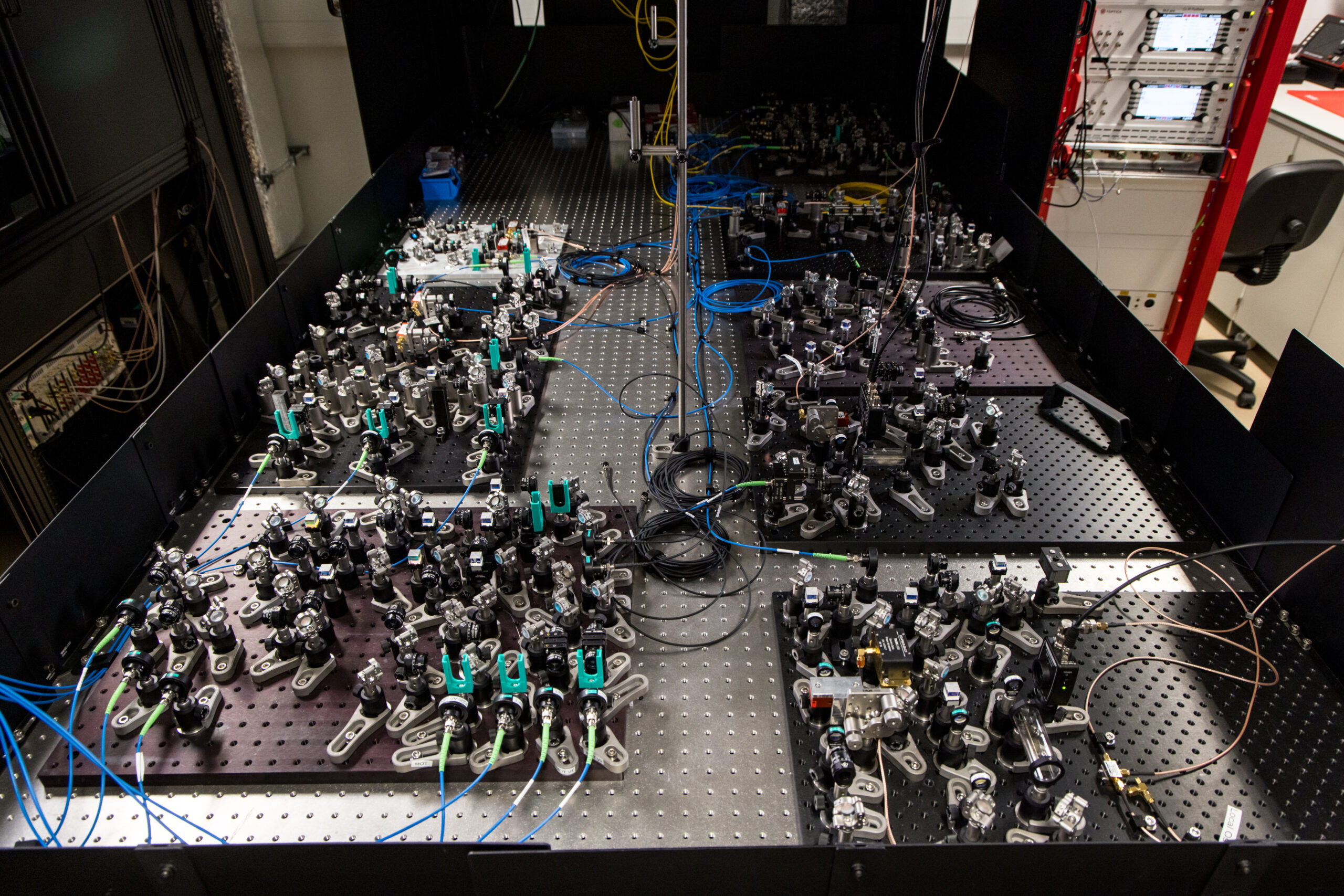

To control atoms takes light. Throw open the black shutters and inside there is a banquet-sized optical table: thick metal drilled with a lattice of holes for mounting all kinds of bits and pieces to manipulate laser light—from collimators to lenses and prisms that fold and shape beams, to acousto-optic and electro-optic modulators that flick beams on and off or change their frequency in nanoseconds—and an orchestra of mirrors mounted on fine-threaded actuators.

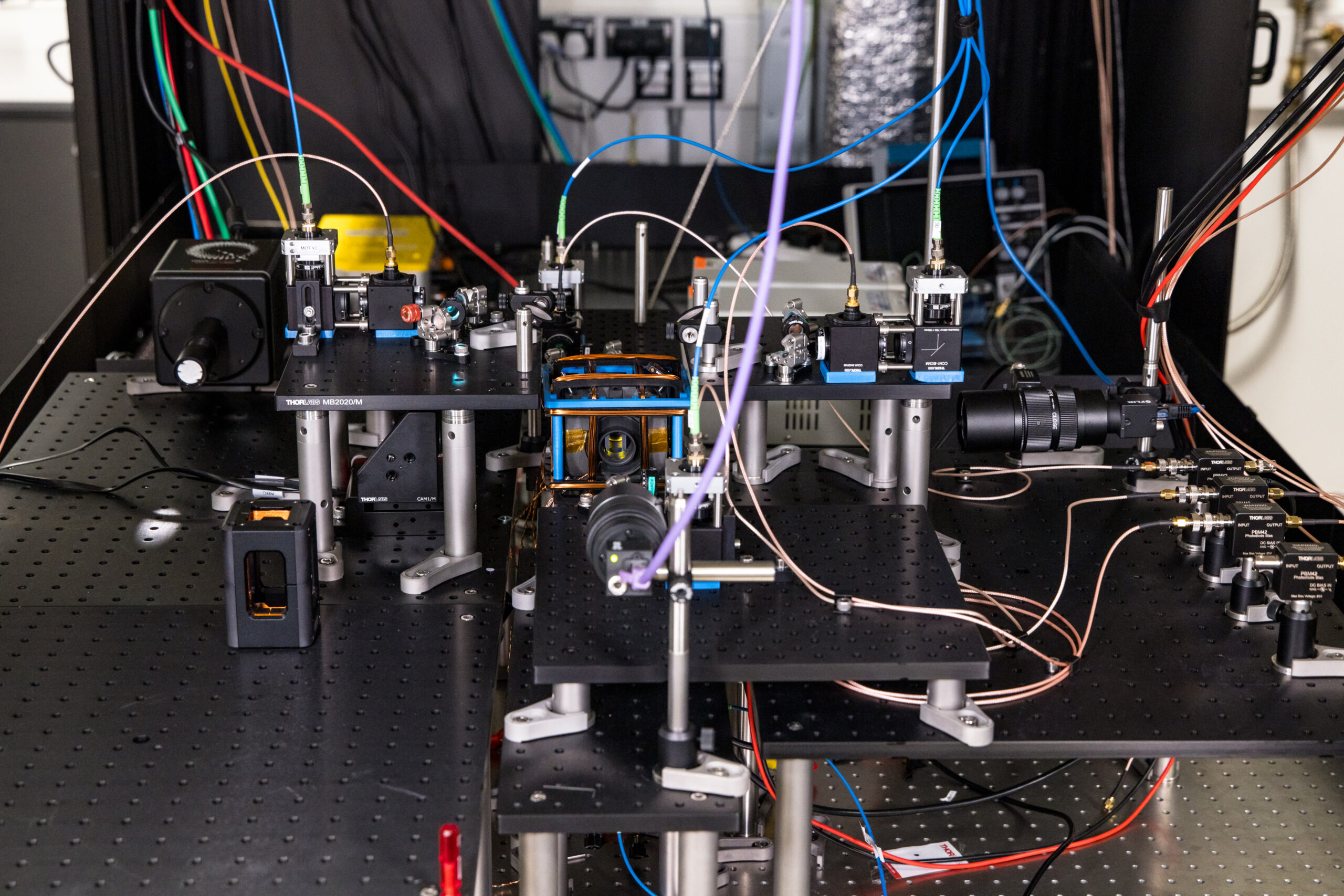

The business end, where laser light does its work, is an 8cm by 2cm glass-fronted vacuum cell. Inside, the NQCC team anticipate trapping hundreds of caesium and rubidium atoms at a time in a neat array by using lasers, which can herd atoms by bombarding them with photons, light particles.

At first the team uses lasers and magnetic fields to herd millions of atoms, even tens of millions of atoms into a ball a few millimetres in diameter, called a magneto-optical-trap. Because molecular and atomic motions are tantamount to heat, the same confining lasers that create this blob also serve to cool the atoms, reaching a few hundred millionths of a degree above absolute zero – colder than outer space.

At this temperature, atoms move at a fraction of the speed they do at room temperature. With the help of extra cooling steps, involving precise tweaking of magnetic fields, laser power and polarisation, the atoms can reach a few millionths of degrees above absolute zero where they can use another set of tightly focused lasers like microscopic tweezers to position them. These tweezing lasers form patterns- lines, grids, even honeycombs- “where an array of several single atoms is held by these optical tweezers as gently as eggs in an egg box,” he explained.

When they want to entangle a pair of atoms, they use a trick called a Rydberg blockade: nearby atoms are briefly brought together and tickled with yet more lasers to form high-energy “Rydberg” states, where atoms can “feel” each other, a little like atomic magnets, so that changing one automatically influences the other. “One atom’s excitation prevents the other’s, so the qubits states become entangled together,” he said. “This entanglement opens the pathway to quantum parallelism, the mechanism to help solve puzzles that normal computers can’t.”

These fleeting interactions – performed over thousandths to millionths of a second – form the logic gates to perform calculations using a fragile but powerful web of atomic correlations, sustained only if the machine is exquisitely isolated from the noisy outside world. The entire apparatus—from the vibration-damped optical table to the thicket of mirrors and modulators—is there to preserve this delicate quantum choreography.

Cameras and single-photon detectors peer at the atoms through viewports, recording the faint fluorescence emitted when an atom changes state, when an electron shifts within it to a lower state. This glow reveals whether the atom represents a 0, a 1. At the end, a sensitive camera takes a picture: glowing dots reveal 1s, dark ones 0s. The pattern is the answer.

The lasers must remain extraordinarily stable for days; photon detection—the only way to read out results— has little tolerance for error when you have to pick up single particles of light from individual atoms; vibration or electromagnetic interference can ruin hours of careful alignment; and it takes time, of the order of a thousandths of a second, to make atoms have close encounters.

While a dozen quantum computers are being tested at the NQCC, nearby on the Harwell campus two commercial companies are also investigating atomic quantum computers: SQALE is the Scalable Quantum Atomic Lattice computing tEstbed, a neutral-atom quantum computing testbed of 16 by 16 arrays of atoms developed by the company Infleqtion, and another is being developed by QuEra Computing. Other teams worldwide are taking a similar approach, with one in Boston, USA, recently describing a 3000 qubit computer, and another in Pasadena unveiling an array of 6,100 atomic qubits.

Simulation and chemistry

Quantum processors—including neutral-atom and molecular arrays- can simulate chemistry in unprecedented detail. These quantum simulations can mimic molecules more faithfully than classical machines. For drug discovery or materials design, this could mean testing how a compound binds, folds or reacts before any synthesis in the lab. The same tools could help uncover new superconductors, catalysts or battery materials tuned for efficiency and sustainability.

For a single atomic species experiment, such as an atom of rubidium or caesium, around five to seven different lasers are required. These can produce pairs of entangled atoms and the resulting quantum processors could tackle problems that stump classical methods: optimising supply chains, traffic systems, or even the training of AI.

Reading out and analysing the results of the quantum processor is done with classical computers. In effect it is a hybrid computer, where quantum co-processors handle the toughest calculations while classical hardware manages the rest. These could become as commonplace as a GPU today is in exascale computers and AI.

Beautiful experimental results from around the world have demonstrated major milestones in making tweezer-based quantum computers real contenders in the zoo of quantum computing possibilities. As with all the rivals, however, scaling the number of qubits while maintaining their fragile quantum states remains a challenge.

“At the NQCC, we are exploring using dual-species architectures, using both rubidium and caesium in a single glass cell to work towards overcoming these challenges. This requires around twice as many lasers, making dual-species experiments naturally more complex,” he said.

For now, though, modest victories matter: by next spring Luke Fernley hopes to have a few hundred atom pairs suspended in a vacuum, each a flickering logic element in a machine that computes with uncertainty itself: he and his fellow quantum computing scientists are learning to compute by choreographing the most delicate dance in physics—one where a single misstep can spoil the whole calculation.

The post How lasers and atoms could change the future of computation appeared first on Science Museum Blog.