The idea of writing the entire human DNA sequence, or genome – once beloved of futurists – could vastly expand biology’s scope. It would let scientists test how genome architecture affects function; help recreate the genomes of our ancestors; engineer bespoke cellular factories for drugs or novel materials; or, ultimately, replace faulty chromosomes wholesale rather than tinkering with genes one by one.

But this ambition has long collided with a mundane problem of scale. A bacterial genome is a minimalist affair: typically, a single circular loop of DNA, a few million genetic “letters” of genetic code long, that can be copied, cut and stitched inside microbial workhorses. A human genome, by contrast, is sprawling.

Your genome comprises 23 pairs of chromosomes—strands of DNA wrapped around proteins—adding up to more than six billion letters.

Human chromosomes are enormous, repetitive and fragile, more like unwieldy books than tidy bacterial pamphlets. Attempt to rewrite one chromosome inside a human cell and the changes will likely affect both copies, and perhaps other chromosomes too.

Now a way around this huge hurdle is unveiled by a study published today in the journal Science from Jason Chin and Julian Sale’s groups at the UKRI-Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge.

Their production line—now demonstrated in several key steps—creates a living test tube to manipulate human chromosomes. First, a chromosome is ferried into a mouse cell from a donor human cell; then it is rewritten in this foreign harbour; finally, it is reinstalled into a recipient human cell.

The work provides a boost for for SynHG, a Wellcome-backed project across British universities to develop the tools needed for synthetic human genomes. Jason Chin, who has worked on a toolkit to reengineer life, explains the significance: ‘As this project develops it will deliver a host of approaches for understanding the relationship between genome sequence and function at scale. Further advances will enable innovative means to produce therapeutic cells and therapeutic molecules.’

The elegance of the method rests on using mouse cells. Inside a mouse cell, an imported human chromosome has no job and no partner. Researchers can carve it up, expand it, or insert synthetic sequence without risking damage to a functioning human genome. Any stray edits remain confined to the mouse cell and, once the redesigned chromosome is ready, it can be transplanted back into a human cell.

Three obstacles had to be cleared: moving intact human chromosomes into mouse stem cells; moving them back; and deleting the now-redundant native copy in the recipient human cell so the final product remains diploid (that is, possesses two copies of each chromosome, as is normal for humans).

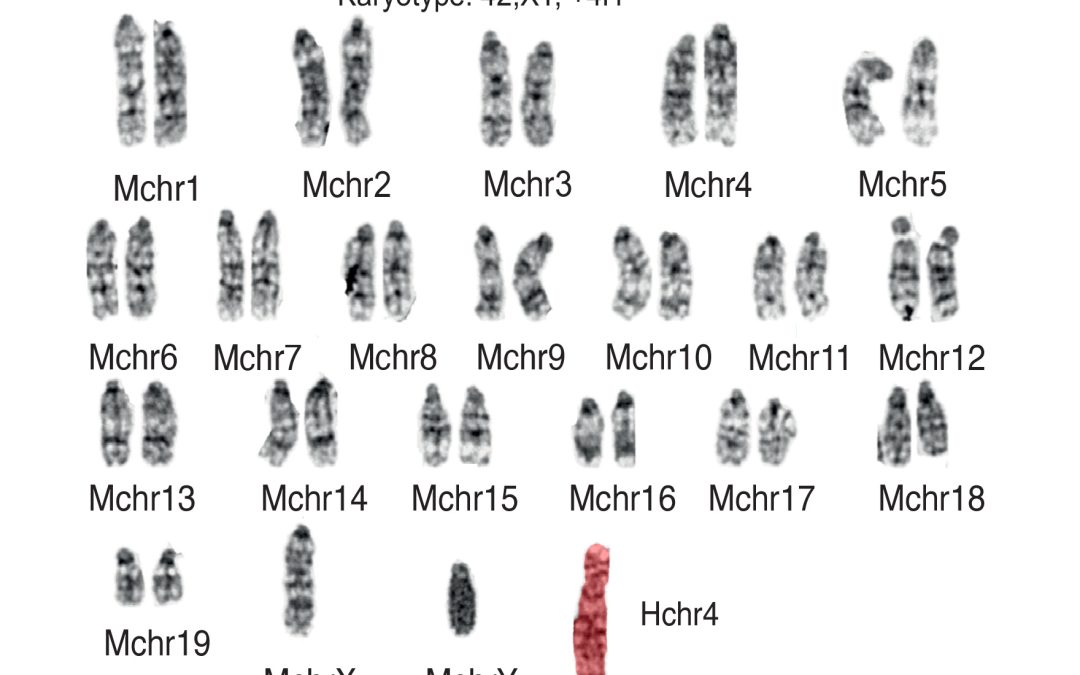

The LMB team shows in the new work that all three can be done with impressive fidelity. Human chromosomes 4 and 21 were shuttled between species without shattering into pieces, only to recombine in unplanned ways, or accumulating more than a smattering of new mutations.

After import back to a human , the team used the gene editing method CRISPR—a programmable genetic scalpel—to nick a chromosome so that when a toxin is added, the targeted chromosome is discarded so only the imported one remains.

Sequencing and chromosome analysis (karyotyping) confirmed structurally intact, diploid genomes, with telomeres—the protective caps at chromosome ends—returning to normal lengths after a few cell cycles.

Julian Sale says this reveals an unappreciated aspect of telomere biology: ‘Mouse chromosomes have much longer telomeres than human chromosomes. We found that the telomeres of human chromosomes get much longer in mouse cells but return to their normal length in human cells. While the net result is that moving chromosomes into mouse cells has no effect on their length when we bring them back to human cells, it uncovers a fascinating aspect of telomere biology.’

This work constitutes the crucial first step in the SynHG pipeline. The next will be more ambitious: using the mouse ‘assembly cell’ to rewrite entire human chromosomes with synthetic sequences—a scale of rewriting DNA that would be perilous inside human cells themselves.

A parallel programme, led by Joy Zhang at the University of Kent, is examining the ethical and geopolitical implications of large-scale genome synthesis in concert with civil-society groups worldwide. As the barriers to the creation of artificial chromosomes fall, questions of purpose, governance and consent will only sharpen.

A fully synthetic human genome may take a decade or longer to create. But this work gives the field something it has never had before: a clean, end-to-end method for taking a human chromosome apart, redesigning it and reinstalling it.

Scientists are beginning not just to read the book of life, but to draft new chapters.

The post How to Build A Synthetic Human Chromosome appeared first on Science Museum Blog.